Learn how to create, manage, and clean up RabbitMQ queues dynamically with MassTransit — ideal for adaptive, message-driven architectures.

(more…)Category: .NET Framework

Automating Git Hooks with Husky.Net

Foreword

During a recent encounter with a React project, I noticed how Git hooks were being used to automatically format code and block non-buildable changes from being committed. That sparked an idea—why not apply the same practice in .NET projects? My search for a solution led me to Husky.Net, a powerful tool designed to automate Git tasks seamlessly within .NET environments.

(more…)Understanding Synchronization Context; Task.ConfigureAwait in Action

Overview

When dealing with asynchronous code, one of the most important concepts that you must have a solid understanding of is synchronization context. Synchronization context is one of the most ignored concepts in the asynchronous programming realm as it is often hard for developers to understand. Today, we will try to simplify things as much as we can. We will have a look at SynchronizationContext class and see how it affects code behavior in action. We will also have a look at one of the most important methods in TPL library, Task.ConfigureAwait().

(more…)Reducing Complexity using Entity Framework Core Owned Types

I came across a very nice feature of Entity Framework Core that I would like to share with you, it is the owned types.

EF Core’s owned types allow you to group fields, that you do not want to appear as a reference, in a separate type.

(more…)My C# Implementation of Basic Linear Algebra Concepts

Overview

Today, I will be sharing with you my C# implementation of the basic linear algebra concepts. This code has been posted to GitHub under a MIT license, so feel free to modify and deal with code without any restrictions or limitations (no guarantees of any kind too.) And please let me know your feedback, comments, suggestions, and corrections.

(more…)Matrix Multiplication in C#; Applying Transformations to Images

Overview

Today I will show you my implementation of matrix multiplication C# and how to use it to apply basic transformations to images like rotation, stretching, flipping, and modifying color density.

Please note that this is not an image processing class. Rather, this article demonstrates in C# three of the core linear algebra concepts, matrix multiplication, dot product, and transformation matrices.

(more…)Unix Time to System.DateTime and Vice Versa

Overview

This code demonstrates how to convert between Unix time (Epoch time) and System.DateTime. This code was previously mentioned in my Protrack API post.

(more…)Building Applications that Can Talk

هذه المقالة متوفرة أيضا باللغة العربية، اقرأها هنا.

Overview

In this article we are going to explore the Speech API library that’s part of the TTS SDK that helps you reading text and speaking it. We’re going to see how to do it programmatically using C# and VB.NET and how to make use of LINQ to make it more interesting. The last part of this article talks about…… won’t tell you more, let’s see!

Introduction

The Speech API library that we are going to use today is represented by the file sapi.dll which’s located in %windir%System32SpeechCommon. This library is not part of the .NET BCL and it’s not even a .NET library, so we’ll use Interoperability to communicate with it (don’t worry, using Visual Studio it’s just a matter of adding a reference to the application.)

Implementation

In this example, we are going to create a Console application that reads text from the user and speaks it. To complete this example, follow these steps:

As an example, we’ll create a simple application that reads user inputs and speaks it. Follow these steps:

- Create a new Console application.

- Add a reference to the Microsoft Speech Object Library (see figure 1.)

Figure 1 - Adding Reference to SpeechLib Library - Write the following code and run your application:

// C# using SpeechLib; static void Main() { Console.WriteLine("Enter the text to read:"); string txt = Console.ReadLine(); Speak(txt); } static void Speak(string text) { SpVoice voice = new SpVoiceClass(); voice.Speak(text, SpeechVoiceSpeakFlags.SVSFDefault); }' VB.NET Imports SpeechLib Sub Main() Console.WriteLine("Enter the text to read:") Dim txt As String = Console.ReadLine() Speak(txt) End Sub Sub Speak(ByVal text As String) Dim voice As New SpVoiceClass() voice.Speak(text, SpeechVoiceSpeakFlags.SVSFDefault) End SubIf you are using Visual Studio 2010 and .NET 4.0 and the application failed to run because of Interop problems, try disabling Interop Type Embedding feature from the properties on the reference SpeechLib.dll.

Building Talking Strings

Next, we’ll make small modifications to the code above to provide an easy way to speak a given System.String. We’ll make use of the Extension Methods feature of LINQ to add the Speak() method created earlier to the System.String. Try the following code:

// C# using SpeechLib; static void Main() { Console.WriteLine("Enter the text to read:"); string txt = Console.ReadLine(); txt.Speak(); } static void Speak(this string text) { SpVoice voice = new SpVoiceClass(); voice.Speak(text, SpeechVoiceSpeakFlags.SVSFDefault); }' VB.NET Imports SpeechLib Imports System.Runtime.CompilerServices Sub Main() Console.WriteLine("Enter the text to read:") Dim txt As String = Console.ReadLine() txt.Speak() End Sub <Extension()> _ Sub Speak(ByVal text As String) Dim voice As New SpVoiceClass() voice.Speak(text, SpeechVoiceSpeakFlags.SVSFDefault) End SubI Love YOU ♥

Let’s make it more interesting. We are going to code a VBScript file that says “I Love YOU” when you call it. To complete this example, these steps:

- Open Notepad.

- Write the following code:

CreateObject("SAPI.SpVoice").Speak "I love YOU!"Of course, CreateObject() is used to create a new instance of an object resides in a given library. SAPI is the name of the Speech API library stored in Windows Registry. SpVoice is the class name.

- Save the file as ‘love.vbs’ (you can use any name you like, just preserve the vbs extension.)

- Now open the file and listen, who is telling that he loves you!

Microsoft Speech API has many voices; two of them are Microsoft Sam (male), the default for Windows XP and Windows 2000, and Microsoft Ann (female), the default for Windows Vista and Windows 7. Read more about Microsoft TTS voices here.

Thanks to our friend, Mohamed Gafar, for providing the VBScript.

.NET Interoperability at a Glance 3 – Unmanaged Code Interoperation

هذه المقالة متوفرة باللغة العربية أيضا، اقرأها هنا.

See more Interoperability examples here.

Contents

Contents of this article:

- Contents

- Read also

- Overview

- Unmanaged Code Interop

- Interop with Native Libraries

- Interop with COM Components

- Interop with ActiveX Controls

- Summary

- Where to go next

Read also

More from this series:

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 1 – Introduction

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 2 – Managed Code Interoperation

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 3 – Unmanaged Code Interoperation

- Video (عربي)

Overview

This is the last article in this series, it talks about unmanaged code interoperation; that’s, interop between .NET code and other code from other technologies (like Windows API, native libraries, COM, ActiveX, etc.)

Be prepared!

Introduction

Managed code interop wasn’t so interesting, so it’s the time for some fun. You might want to call some Win32 API functions, or it might be interesting if you make use of old, but useful, COM components. Let’s start!

Unmanaged Code Interop

Managed code interoperation isn’t so interesting, but this is. Unmanaged interoperation is not easy as the managed interop, and it’s also much difficult and much harder to implement. In unmanaged code interoperation, the first system is the .NET code; the other system might be any other technology including Win32 API, COM, ActiveX, etc. Simply, unmanaged interop can be seen in three major forms:

- Interoperation with Native Libraries.

- Interoperation with COM components.

- Interoperation with ActiveX.

Interop with Native Libraries

This is the most famous form of .NET interop with unmanaged code. We usually call this technique, Platform Invocation, or simply PInvoke. Platform Invocation or PInvoke refers to the technique used to call functions of native unmanaged libraries such as the Windows API.

To PInvoke a function, you must declare it in your .NET code. That declaration is called the Managed Signature. To complete the managed signature, you need to know the following information about the function:

- The library file which the function resides in.

- Function name.

- Return type of the function.

- Input parameters.

- Other relevant information such as encoding.

Here comes a question, how could we handle types in unmanaged code that aren’t available in .NET (e.g. BOOL, LPCTSTR, etc.)?

The solution is in Marshaling. Marshaling is the process of converting unmanaged types into managed and vice versa (see figure 1.) That conversion can be done in many ways based on the type to be converted. For example, BOOL can simply be converted to System.Boolean, and LPCTSTR can be converted to System.String, System.Text.StringBuilder, or even System.Char[]. Compound types (like structures and unions) are usually don’t have counterparts in .NET code and thus you need to create them manually. Read our book about marshaling here.

- Figure 1 – The Marshaling Process

To understand P/Invoke very well, we’ll take an example. The following code switches between mouse button functions, making the right button acts as the primary key, while making the left button acts as the secondary key.

In this code, we’ll use the SwapMouseButtons() function of the Win32 API which resides in user32.dll library and has the following declaration:

BOOL SwapMouseButton(

BOOL fSwap

);

Of course, the first thing is to create the managed signature (the PInvoke method) of the function in .NET:

// C#

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.DllImport("user32.dll")]

static extern bool SwapMouseButton(bool fSwap);

' VB.NET

Declare Auto Function SwapMouseButton Lib "user32.dll" _

(ByVal fSwap As Boolean) As Boolean

Then we can call it:

// C#

public void MakeRightButtonPrimary()

{

SwapMouseButton(true);

}

public void MakeLeftButtonPrimary()

{

SwapMouseButton(false);

}

' VB.NET

Public Sub MakeRightButtonPrimary()

SwapMouseButton(True)

End Sub

Public Sub MakeLeftButtonPrimary()

SwapMouseButton(False)

End Sub

Interop with COM Components

The other form of unmanaged interoperation is the COM Interop. COM Interop is very large and much harder than P/Invoke and it has many ways to implement. For the sake of our discussion (this is just a sneak look at the technique,) we’ll take a very simple example.

COM Interop includes all COM-related technologies such as OLE, COM+, ActiveX, etc.

Of course, you can’t talk directly to unmanaged code. As you’ve seen in Platform Invocation, you have to declare your functions and types in your .NET code. How can you do this? Actually, Visual Studio helps you almost with everything so that you simply to include a COM-component in your .NET application, you go to the COM tab of the Add Reference dialog (figure 2) and select the COM component that you wish to add to your project, and you’re ready to use it!

- Figure 2 – Adding Reference to SpeechLib Library

When you add a COM-component to your .NET application, Visual Studio automatically declares all functions and types in that library for you. How? It creates a Proxy library (i.e. assembly) that contains the managed signatures of the unmanaged types and functions of the COM component and adds it to your .NET application.

The proxy acts as an intermediary layer between your .NET assembly and the COM-component. Therefore, your code actually calls the managed signatures in the proxy library that forwards your calls to the COM-component and returns back the results.

Keep in mind that proxy libraries also called Primary Interop Assemblies (PIAs) and Runtime Callable Wrappers (RCWs.)

Best mentioning that Visual Studio 2010 (or technically, .NET 4.0) has lots of improved features for interop. For example, now you don’t have to ship a proxy/PIA/RCW assembly along with your executable since the information in this assembly can now be embedded into your executable; this is what called, Interop Type Embedding.

Of course, you can create your managed signatures manually, however, it’s not recommended especially if you don’t have enough knowledge of the underlying technology and the marshaling of functions and types (you know what’s being said about COM!)

As an example, we’ll create a simple application that reads user inputs and speaks it. Follow these steps:

- Create a new Console application.

- Add a reference to the Microsoft Speech Object Library (see figure 2.)

- Write the following code and run your application:

// C#

using SpeechLib;

static void Main()

{

Console.WriteLine("Enter the text to read:");

string txt = Console.ReadLine();

Speak(txt);

}

static void Speak(string text)

{

SpVoice voice = new SpVoiceClass();

voice.Speak(text, SpeechVoiceSpeakFlags.SVSFDefault);

}

' VB.NET

Imports SpeechLib

Sub Main()

Console.WriteLine("Enter the text to read:")

Dim txt As String = Console.ReadLine()

Speak(txt)

End Sub

Sub Speak(ByVal text As String)

Dim voice As New SpVoiceClass()

voice.Speak(text, SpeechVoiceSpeakFlags.SVSFDefault)

End Sub

If you are using Visual Studio 2010 and .NET 4.0 and the application failed to run because of Interop problems, try disabling Interop Type Embedding feature from the properties on the reference SpeechLib.dll.

Interop with ActiveX Controls

ActiveX is no more than a COM component that has an interface. Therefore, nearly all what we have said about COM components in the last section can be applied here except the way we add ActiveX components to our .NET applications.

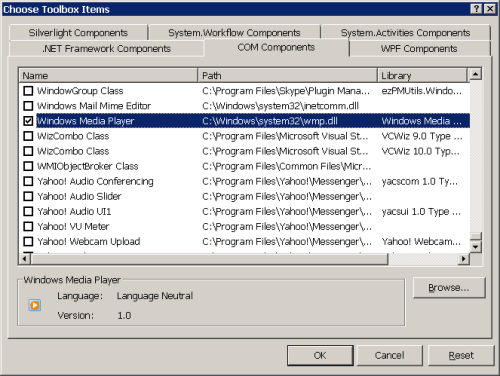

To add an ActiveX control to your .NET application, you can right-click the Toolbox, select Choose Toolbox Items, switch to the COM Components tab and select the controls that you wish to use in your application (see figure 3.)

- Figure 3 – Adding WMP Control to the Toolbox

Another way is to use the aximp.exe tool provided by the .NET Framework (located in Program FilesMicrosoft SDKsWindowsv7.0Abin) to create the proxy assembly for the ActiveX component:

aximp.exe "C:WindowsSystem32wmp.dll"

Not surprisingly, you can create the proxy using the way for COM components discussed in the previous section, however, you won’t see any control that can be added to your form! That way creates control class wrappers for unmanaged ActiveX controls in that component.

Summary

So, unmanaged code interoperation comes in two forms: 1) PInvoke: interop with native libraries including the Windows API 2) COM-interop which includes all COM-related technologies like COM+, OLE, and ActiveX.

To PInvoke a method, you must declare it in your .NET code. The declaration must include 1) the library which the function resides in 2) the return type of the function 3) function arguments.

COM-interop also need function and type declaration and that’s usually done for you by the Visual Studio which creates a proxy (also called RCW and PIA) assembly that contains managed definitions of the unmanaged functions and types and adds it to your project.

Where to go next

Read more about Interoperability here.

More from this series:

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 1 – Introduction

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 2 – Managed Code Interoperation

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 3 – Unmanaged Code Interoperation

- Video (عربي)

.NET Interoperability at a Glance 2 – Managed Code Interoperation

هذه المقالة متوفرة أيضا باللغة العربية، اقرأها هنا.

See more Interoperability examples here.

Contents

Contents of this article:

- Contents

- Read also

- Overview

- Introduction

- Forms of Interop

- Managed Code Interop

- Summary

- Where to go next

Read also

More from this series:

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 1 – Introduction

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 2 – Managed Code Interoperation

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 3 – Unmanaged Code Interoperation

Overview

In the previous article, you learnt what interoperability is and how it relates to the .NET Framework. In this article, we’re going to talk about the first form of interoperability, the Managed Code Interop. In the next article, we’ll talk about the other forms.

Introduction

So, to understand Interoperation well in the .NET Framework, you must see it in action. In this article, we’ll talk about the first form of .NET interoperability and see how to implement it using the available tools.

Just a reminder, Interoperability is the process of communication between two separate systems. In .NET Interop, the first system is always the .NET Framework; the other system might be any other technology.

Forms of Interop

Interoperability in .NET Framework has two forms:

- Managed Code Interoperability

- Unmanaged Code Interoperability

Next, we have a short discussion of each of the forms.

Managed Code Interop

This was one of the main goals of .NET Framework. Managed Code Interoperability means that you can easily communicate with any other .NET assembly no matter what language used to build that assembly.

Not surprisingly, because of the nature of .NET Framework and its runtime engine (the CLR,) .NET code supposed to be called Managed Code, while any other code is unmanaged.

To see this in action, let’s try this:

- Create a new Console application in the language you like (C#/VB.NET.)

- Add a new Class Library project to the solution and choose another language other than the one used in the first project.

- In the Class Library project, add the following code (choose the suitable project):

// C# public static class Hello { public static string SayHello(string name) { return "Hello, " + name; } }' VB.NET Public Module Hello Public Function SayHello(ByVal name As String) As String Return "Hello, " & name End Function End Module - Now, go back to the Console application. Our goal is to call the function we have added to the other project. To do this, you must first add a reference to the library in the first project. Right-click the Console project in Solution Explorer and choose Add Reference to open the Add Reference dialog (figure 1.) Go to the Projects tab and select the class library project to add it.

Figure 1 - Add Reference to a friend project - Now you can add the following code to the Console application to call the SayHello() function of the class library.

// C# static void Main() { Console.WriteLine(ClassLibrary1.Hello.SayHello("Mohammad Elsheimy")); }' VB.NET Sub Main() Console.WriteLine(ClassLibrary1.Hello.SayHello("Mohammad Elsheimy")) End Sub

How this happened? How could we use the VB.NET module in C# which is not available there (or the C#’s static class in VB which is not available there too)?

Not just that, but you can inherit C# classes from VB.NET (and vice versa) and do all you like as if both were created using the same language. The secret behind this is the Common Intermediate Language (CIL.)

When you compile your project, the compiler actually doesn’t convert your C#/VB.NET code to instructions in the Machine language. Rather, it converts your code to another language of the .NET Framework, which is the Common Intermediate Language. The Common Intermediate Language, or simply CIL, is the main language of .NET Framework which inherits all the functionalities of the framework, and which all other .NET languages when compiled are converted to it.

So, the CIL fits as a middle layer between your .NET language and the machine language. When you compile your project, the compiler converts your code to CIL statements and emits them in assembly file. In runtime, the compiler reads the CIL from the assembly and converts them to machine-readable statements.

How CIL helps in interoperation? The communication between .NET assemblies is now done through the CIL of the assemblies. Therefore, you don’t need to be aware of structures and statements that are not available in your language since every statement for any .NET language has a counterpart in IL. For example, both the C# static class and VB.NET module convert to CIL static abstract class (see figure 2.)

Managed Interop is not restricted to C# and VB.NET only; it’s about all languages run inside the CLR (i.e. based on .NET Framework.)

If we have a sneak look at the CIL generated from the Hello class which is nearly the same from both VB.NET and C#, we would see the following code:

.class public abstract auto ansi sealed beforefieldinit ClassLibrary1.Hello

extends [mscorlib]System.Object

{

.method public hidebysig static string SayHello(string name) cil managed

{

// Code size 12 (0xc)

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ldstr "Hello, "

IL_0005: ldarg.0

IL_0006: call string [mscorlib]System.String::Concat(string,

string)

IL_000b: ret

} // end of method Hello::SayHello

} // end of class ClassLibrary1.Hello

On the other hand, this is the code generated from the Main function (which is also the same from VB.NET/C#):

.class public abstract auto ansi sealed beforefieldinit ConsoleApplication1.Program

extends [mscorlib]System.Object

{

.method private hidebysig static void Main() cil managed

{

.entrypoint

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ldstr "Mohammad Elsheimy"

IL_0005: call string [ClassLibrary1]ClassLibrary1.Hello::SayHello(string)

IL_000a: call void [mscorlib]System.Console::WriteLine(string)

IL_000f: ret

} // end of method Program::Main

} // end of class ConsoleApplication1.Program

You can use the ILDasm.exe tool to get the CIL code of an assembly. This tool is located in Program FilesMicrosoft SDKsWindows<version>bin.

Here comes a question, is there CIL developers? Could we write the CIL directly and build it into .NET assembly? Why we can’t find much (if not any) CIL developers? You can extract the answer from the CIL code itself. As you see, CIL is not so friendly and its statements are not so clear. Plus, if we could use common languages to generate the CIL, we we’d like to program in CIL directly? So it’s better to leave the CIL for the compiler.

Now, let’s see the other form of .NET interoperation, Unmanaged Code Interoperability.

Summary

So, the secret of Managed Code Interoperation falls in the Common Intermediate Language or CIL. When you compile your code, the compiler converts your C#/VB.NET (or any other .NET language) to CIL instructions and saves them in the assembly, and that’s the secret. The linking between .NET assemblies of different languages relies on the fact that the linking is actually done between CILs of the assemblies. The assembly code doesn’t (usually) have any clue about the language used to develop it. In the runtime, the compiler reads those instructions and converts them to machine instructions and execute them.

Next, we’ll talk about the other form of .NET Interoperation, it’s the interoperation with unmanaged code.

Where to go next

Read more about Interoperability here.

More from this series:

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 1 – Introduction

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 2 – Managed Code Interoperation

- .NET Interoperability at a Glance 3 – Unmanaged Code Interoperation